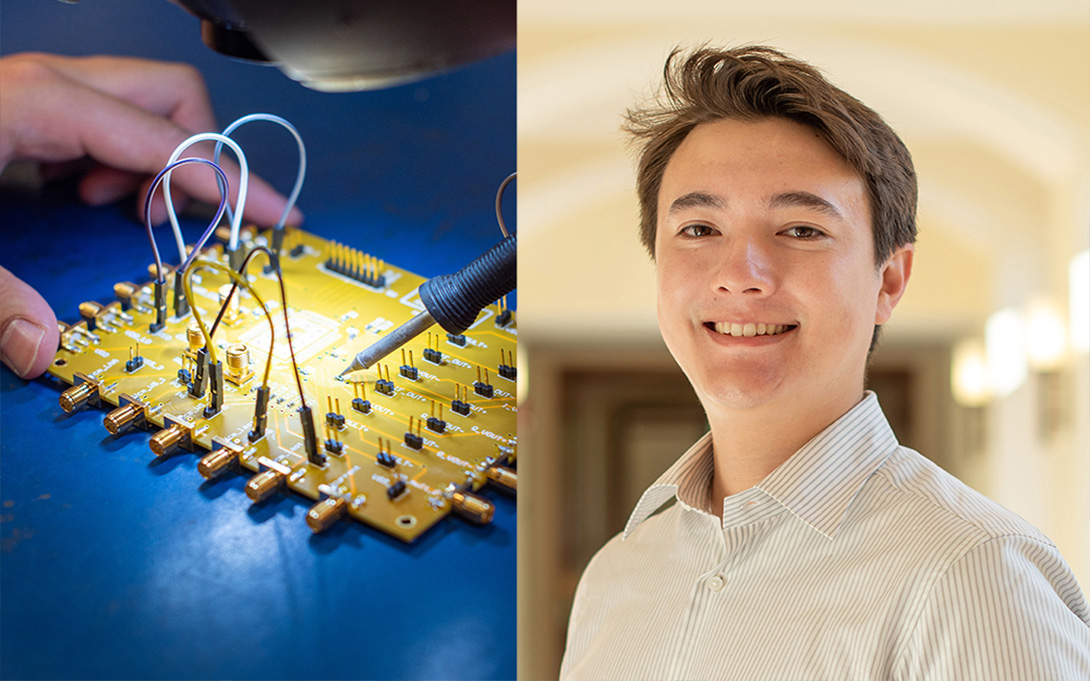

Through the Ford School’s Science, Technology, and Public Policy (STPP) Program, ECE PhD student Trevor Odelberg is studying how engineers can take better responsibility for the way their research impacts society.

As the character Dr. Ian Malcolm famously says in Jurassic Park, “Your scientists were so preoccupied with whether or not they could, they didn’t stop to think if they should.”

Like Malcolm, many believe that scientists and engineers bear a responsibility not only for what they choose to create, but how their work is used to impact society. Yet engineering classrooms are traditionally focused on how to achieve something, rather than the ethical implications of that achievement. For this reason, PhD student Trevor Odelberg decided to enroll in the Science, Technology, and Public Policy (STPP) Program offered through the Gerald R. Ford School of Public Policy at U-M.

“This program has completely changed my perspective, and it’s given me a greater appreciation of my work,” Odelberg said. “We as scientists and engineers need to be better about being stewards for our technology and making sure that it’s impacting people in the right way.”

Odelberg’s research is focused on RF/analog IC design, wireless communication, digital signal processing, and low-power circuit design. He’s the recipient of a National Defense Science and Engineering Graduate Fellowship for his work on low power batteryless circuits, and he’s advised by Prof. David Wentlzoff. But his focus in the STPP is to examine the intersection of science and technology with public policy, as well as the role scientists and engineers play regarding how their work is implemented in society.

“We can innovate and do really cool things to help people, but we have to make sure we’re mitigating the potential harm that can come from technology as well,” Odelberg said.

While there have been many societal benefits to new technologies — from advancing medical diagnosis and treatment to improving access to education and information — they can also have negative consequences that often disproportionately harm marginalized communities. For example, facial recognition software is better at recognizing white faces than Black faces, which puts Black people more at risk for wrongful arrest. Job search platforms have been shown to rank less qualified male applicants higher than more qualified female applicants. Auto-captioning systems, which are important for accessibility, vary widely in accuracy depending on the accent of the speaker.

Odelberg was especially inspired to enroll in the STPP after watching the Facebook congressional hearings. The goal of the hearings was to investigate how Facebook was addressing the many harmful effects of its platform — from empowering the spread of misinformation to its damaging impacts on mental health, as well as the privacy concerns of how it gathers and shares user data — but most people may remember the hearings for how the senators struggled to understand the most basic aspects of the platform.

“I really wished an educated engineer or a technical person was there to ask those harder hitting questions,” Odelberg said. “I think sometimes as scientists, we think our work is apolitical and we don’t have to worry about the bigger world, but that’s not true. We need to be able to engage with policy and the politics of our work, because otherwise, someone else will do it for us, and they may not know as much about it as we do.”

Training students to effectively use scientific and technical knowledge to inform public policy processes for societal benefit, either in policy careers or in academia, is the main goal of the STPP. Students come together from the natural and physical sciences, engineering, public policy, public health, law, information, environmental studies, and more to debate a wide variety of ethical issues surrounding STEM and STEM policies.

“Communities are increasingly concerned they do not benefit from research and development, and that the risks of emerging technologies may outweigh their benefits,” said Molly Kleinman, the Managing Director of the STPP. “We bring a rigorous interdisciplinary lens to understanding these concerns, and translating them to policymakers, engineers, scientists, and civil society to produce more equitable and just science, technology, and related policies.”

The STPP, which began in 2006, is open to graduate students from all disciplines — no background in science or policy is required. It recently added a community partnerships program, which aims to bring community wisdom and expertise into science and technology policy decisions.

“Members of affected communities often have important knowledge about how to make sure that science and technology will benefit their community and be fair, but are often excluded from the policy process,” Kleinman said. “We respect and value this expertise and are dedicated to bringing these voices into public and policy conversations about science and technology.”

Odelberg hopes the STPP could also help influence traditional engineering curriculum, ensuring that the new generation of engineers are trained to consider these issues regardless of where they end up.

“How can we make ethical engineers? How can we alter STEM education to be less rigid?” he said. “Even if you go on to work at a big tech company, you still need to know this stuff, because you might have a chance to touch a lot of people in that position. No matter where you end up working, there’s always ways to be a good steward.”

Odelberg is currently working with the STPP Student Research Corps, a newer program within the Ford School where STPP students collaborate out of the classroom with community partners to write memos and conduct applied research for real policy issues in the community.

This semester, Odelberg will be working with researchers in the Ford School and Joshua Edmonds, the Director of Digital Inclusion of the City of Detroit, on the municipal fiber internet project in the City of Detroit. This project aims to deliver high speed fiber optic internet access to every home and business in a Detroit neighborhood that’s most in need of improved access and reliability.

“This is a great project for me, because I am able to take my technical background in ECE and apply it to a real-world problem locally in Detroit,” Odelberg said.

This article was written by Hayley Hanway, College of Engineering

More news from the Ford School