By Elana Goldenkoff

I had assumed there was a technical solution to gerrymandering. I figured there surely existed an algorithm or statistical method for drawing equally populated districts that were fair and non-partisan. I thought the process could even be as simple as: look at the maps that elected politicians in Lansing created, and then do the opposite. But as we learn in our Science, Technology, and Public Policy courses, there is no such thing as a purely technical problem.

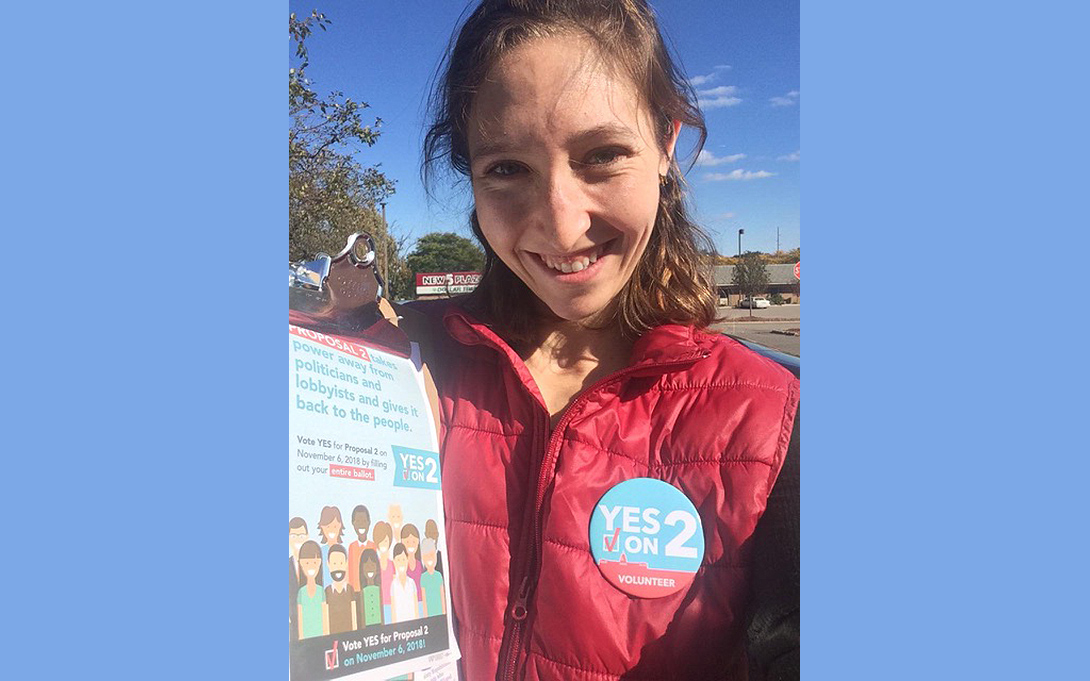

That is why I knocked on hundreds of doors for Voters Not Politicians prior to the 2018 election. This grassroots organization fought for a ballot initiative which would remove redistricting control from the state legislature and instead create an independent citizen commission to transparently redraw political maps after each census. The proposal passed 61.28% to 38.72% as most voters wanted to separate partisanship from redistricting. Michiganders strongly believed that a commission could ensure equity and fair representation while also guaranteeing that districts are geographically contiguous, reasonably compact, adhere to the Voting Rights Act, preserve communities of interest, reflect diversity, neither favor nor disfavor incumbents, and promote electoral competitiveness.

Now I realized how difficult, if not impossible, a task this is for the commissioners. This past month I participated in a joint MSU/UM student effort to support five Michigan Independent Citizens Redistricting Commission public hearings across the state. We helped constituents explore the 20+ proposed plans for state house, state senate, and congressional maps, deliver online comments, and sign up to speak in person.

I staffed three public hearings in Detroit, Lansing, and Flint. While listening to the unique concerns of individuals in each part of the state, I learned how redistricting would impact the voice and political representation of various stakeholder groups. For example, maps can dilute the power of minoritized voters by “packing” communities into few districts or “cracking” them by splitting up neighborhoods across many districts (check out this NYT infographic on the art of gerrymandering). The proposed maps increase the number of Detroit districts where Black voters make up a plurality of the population but reduce the number of districts where Black voters are a majority by pairing them with whiter suburban regions. Activists expressed concerns that these maps would disenfranchise Black voters during primary elections even if the districts stayed Democratic in general elections.

In Lansing, rural residents advocated to remain separate from districts that covered urban areas and college cities such as Ann Arbor and East Lansing. They feared their votes and their needs would be drowned out by those in larger population centers. Meanwhile, water concerns defined ‘communities of interest’ at the Flint meeting. Residents from Midland, Bay City and Saginaw wanted to preserve a district covering their shared watershed which flooded earlier this year causing severe damage. Flint constituents fought to assure their own representative district as they are still managing the fallout from the lead crisis.

There is no such thing as a mathematically perfect electoral map. However, the commission can do its best to design a politically and socially acceptable map by making decisions transparent, giving everyone a voice, and listening to citizens’ feedback. This is ultimately what voters in 2018 wanted: political power restored to the people.

You can view the proposed maps and provide public comment to the redistricting commission through Dec. 30th.